May 29, 2020, should have been a pride-filled day as I, a Black daughter of immigrants, would confer a master's degree from MIT.

Instead, I grieved as I watched news coverage of the murder of George Floyd four days prior by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. For nine minutes and 29 seconds, Chauvin kneeled on the back of Floyd’s neck, as Floyd uttered “I can’t breathe” multiple times until his final breath. The phrase, “I can’t breathe,” was also said by Eric Garner, Manuel Ellis, and Elijah McClain under duress before being killed by police. Awareness of police violence was not new to me – years earlier, a loved one had been wrongfully tackled and jailed – but that day, something shifted in me.

To read a version of this story in Spanish click here. Haz clic aquí para leer esta columna de opinión en español.

Initially, this shift was limited to questioning the role of police on my campus and in cities in general. Like many of my peers, I began to embrace a stance that called not for police reform, but police abolition. We considered that given the history of policing in this country, which was developed to preserve the racial hierarchy of the slavery and Jim Crow eras, a solution to stop police violence was to reduce reliance on police by investing in public social infrastructure such as affordable housing and mental healthcare that could address root causes of crime. But proponents of abolition philosophy felt we could go even further: not only could we end police, but we could close prisons and build new justice systems and institutions rooted in care and restorative processes. I know for many, this is a shocking and extreme stance. When I first heard about it, I certainly had my doubts about whether our society could really operate without prisons. After all, I had grown up with the usual conceptions that prisons make us safer and they are ‘necessary’, ‘rehabilitative’, spaces for people who do crimes.

But then I learned about a pattern of prisons, jails and detention centers being placed in locations where environmental hazards such as toxic landfills, floods and extreme heat was the norm, threatening the health and well-being of incarcerated people and staff – a reality that counters any prospect of true rehabilitation in these spaces. I also spoke with dozens of formerly incarcerated people who explained that the physical and mental suffering they endured in prisons from both environmental and social factors left them in much worse shape than before their sentences.

It became clearer to me how, as researchers Ki’Amber Thompson, Erik Kojola and David Pellow have described, “I can’t breathe” reflects both a cry against physical police violence, but also state-sanctioned environmental injustice that limits and shortens breath in prisons and other carceral facilities. If we think about environmental justice as everyone’s right to exist in safe and healthy places, prisons in the U.S. are a direct threat to that vision and it becomes clearer why we need prison abolition alongside police abolition. After understanding the problem, we can start to imagine alternatives that keep us safe and bring us toward a world where we can all breathe.

Environmental injustice in prisons

I devoted my doctoral research at MIT to studying environmental injustice in prisons across a variety of hazards.

I also spoke with dozens of formerly incarcerated people who explained that the physical and mental suffering they endured in prisons from both environmental and social factors left them in much worse shape than before their sentences.

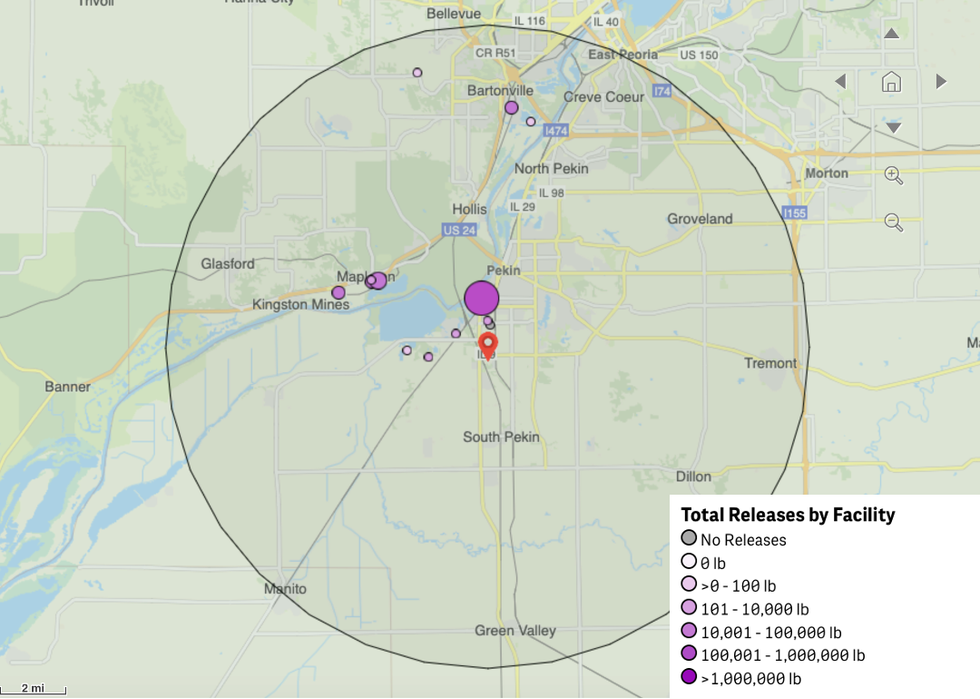

One prevalent hazard I studied was air pollution. Incarcerated populations may be exposed to numerous sources of air pollution, as many prisons are close to industrial activity, toxic waste facilities and places where wildfires are common. When I interviewed formerly incarcerated people about their experiences of environmental hazards, one woman who had been in prison in Pekin, Illinois, described what it was like to live in a place where at least 15 facilities in the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory pollute the air, water and land with chemicals. “We were right across the street, literally, right across the street from a power plant that was just belching this sulfurous smelling stuff. I don't know what it was. And I know that I have asthma. And that was really aggravated there,” she said. “There were times when we just couldn't go outside … because it wasn't just the smell you'd breathe in—it was like your lungs would … hurt.”

Fifteen facilities (indicated by purple dots) in the U.S. EPA's Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program that are within a 10 mile radius of the federal correctional institution, Pekin — a medium-security prison in Illinois (indicated by red marker).

Credit: Ufuoma Ovienmhada via TRI Toxics Tracker

This type of exposure is not pure coincidence. In certain regions facing economic hardship, land formerly used in agriculture, mining or industrial operations that have left behind legacies of air, soil and water pollution have been repurposed for prisons under the faulty premise that the prison will bring new jobs and prosperity. As I write this, Congressman Hal Rogers is championing a $500 million dollar effort to build two new Federal prisons in Letcher County, Kentucky, on a contaminated former coal mine, despite declining rates of crime and significant community opposition.

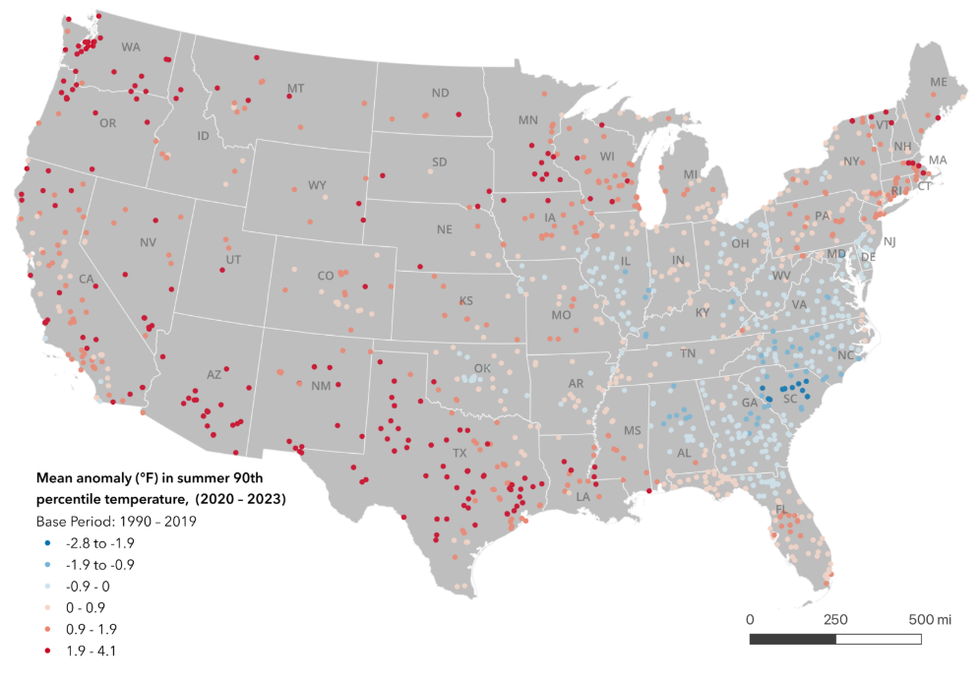

Carceral facilities are also exposed to extreme heat. On average from 2020 to 2023, prisons across the U.S. experienced air temperatures of 94°F at least 10 days of the summer. Prisons are particularly vulnerable to heat exposure due to their aging infrastructure. The majority of prisons in the U.S. were built before 2000, with some built as early as the 1800s. As a result, they often have absent or outdated cooling, heating, and ventilation systems. Several people I’ve interviewed described laying on the cell floor in pools of water from the toilet to stay cool in hot facilities without air conditioning. Climate change is only making matters worse as 70% of prisons are experiencing worse temperature extremes than before. Further, the lack of universal policies in state or federal prisons for responding to climate hazards, such as hurricanes and wildfires, makes it hard to protect those who live in them. As one interviewee remarked about a wildfire event that occurred while they were incarcerated, “the only thing that we [heard] was that in case the fire did get close, we weren’t gonna go nowhere, we were gonna be in our cells…maybe the staff was going to be let out to go home… but we in our minds knew they weren’t going to try and ship us or transport us to a different location to protect us.”

Red dots indicate that a prison has been hotter in recent years (2020 - 2023) than the historical average from 1990 - 2019.

Credit: Ufuoma Ovienmhada

As a consequence of exposure to environmental hazards, people in prisons, jails, and detention centers can develop respiratory and cardiovascular diseases that can, quite literally, affect their ability to breathe, and even lead to premature death. The fact that environmental injustice is widespread in carceral facilities reveals that the suffocation of marginalized bodies in the U.S. behind bars is in many cases by design, not an accidental byproduct. This highlights the need for a strategy that can address such an intentionally neglectful and deadly system.

Toward a world where we can breathe

At this point, one might argue that reforms such as repairs to prison infrastructure might solve the problem. However, many formerly incarcerated have witnessed first-hand money received for building repairs that were never completed. Formerly incarcerated people also highlight the ways that ‘upgrades’ such as air conditioning that are seemingly positive can create new forms of environmental injustice in prisons. As one person I spoke to in my research explained, “I know [it] happens in Santa Fe a lot where they use air conditioning to punish people by sticking them in solitary confinement where it’s really cold cells… People actually died in those conditions.” In another case, someone recounted experiences of trying to get escorted to ‘respite’, an air-conditioned room that people are supposed to be able to access 24/7 when they feel too hot, but being denied by guards who wanted people to suffer in the boiling hot prison cells. Beyond environmental hazards, the dozens of formerly incarcerated people that I’ve interviewed also make clear that prisons in the U.S. are also toxic due to the ways that they deprive people of resources and agency, subject people to poor healthcare, and force people into low and no-wage labor.

As a consequence of exposure to environmental hazards, people in prisons, jails, and detention centers can develop respiratory and cardiovascular diseases that can, quite literally, affect their ability to breathe, and even lead to premature death.

These realities showcase why appealing to the state to address environmental injustice in prisons through piecemeal reforms such as installing air conditioning is not a foolproof solution and delays the attainment of a world where everyone, especially those at the margins, can breathe and be free from all forms of environmental violence.

What, then, can we do? As I dug deeper into this issue, I came across the work of sociologist Ki’Amber Thompson, who introduced the concept of ‘abolitionist environmental justice’. Thompson describes it as a push to replace our justice system's logic of punishment, retribution and extraction with policies and practices that affirm the value and dignity of all human and nonhuman lives. She asserts that these kinds of practices can help us move “toward a world where we can all breathe” as a result of liberation from police, prisons, and pollution. Abolitionist environmental justice directly responds to the idea that the current prison system in the U.S. is incompatible with the vision of environmental justice as “the right to live, work, play, pray, and do time” in safe and healthy places.

Enacting an abolitionist environmental justice may sound idealistic, but it’s already happening across the country. For example, the Campaign to Fight Toxic Prisons (FTP) is an advocacy group that connects grassroots organizers to work for the equity and safety of incarcerated people by conducting campaigns urging prison officials to prepare in advance of disasters, and working to prevent the construction of new toxic prisons that would negatively impact incarcerated populations or destroy important ecosystems. FTP also supports campaigns like #Our444million which champion the idea that communities should get to spend money on real, sustainable economic development instead of job creation based on mass incarceration.

Californians United for a Responsible Budget (CURB) is another example of a coalition working to decarcerate, close prisons and shift spending toward healthy community investments such as workforce development, affordable housing and drug treatment programs as strategies to reduce crime. CURB takes into account environmental risk factors, prison operating costs and other factors related to prisoner’s well-being, to select prisons to prioritize for closure.

The idea of increasing investment in social infrastructure to support crime prevention is agreeable enough, but people may struggle to think about how our society will deal with violent crime that occurs in the absence of prisons. Geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore addresses this question with the following quote:

"Abolition is about presence, not absence. It's about building life-affirming institutions."

This means that closing and divesting from prisons must be paired with investment in restorative and transformative community infrastructure that can address a variety of conflicts and harm that arises. There are numerous examples of activists experimenting with ways to practice accountability for people who do harm in a way that preserves the dignity of both the harm-doer and the victim. This includes community service that relates to the type of harm done, facilitated dialogue between victims and offenders and family conferencing where people impacted by the harm brainstorm the resources they need and how it can be repaired. These types of practices could be particularly useful given that a significant amount of crime occurs amidst existing relationships; nearly a third of homicide victims are killed by people they know and most sexual abuse victims know their perpetrator. Part of a practice of transformative justice can also include removing unrepentant or repeated harm-doers from spaces where they have access or power to do harm. Still, in these cases, people should not be dehumanized by placing them in toxic environments where they will not actually rehabilitate into holistically better people.

While prison and police abolition may seem like a challenging and unwieldy endeavor, it's one we must take seriously and work toward as the only way to prevent outcomes of suffocation whether at the hands of police or through toxic prisons. Environmental justice needs abolition so that we can move toward a world where we can all breathe.

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship, a partnership between Environmental Health News and Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.

- The disturbing link between environmental racism and criminalization ›

- LISTEN: Ufuoma Ovienmhada on toxic prisons ›